So you’ve recently been diagnosed with a prolapse, or you’re convinced that your bladder is falling out of your body. First, you are NOT broken! Pelvic Organ Prolapse is a lot more common than you might think. Second, Cochrane Review of medical journals and studies, show that Pelvic Health Physiotherapy is the gold standard in care for this common condition. If you’re already under the care of a pelvic health physiotherapist, congratulations! If not, just click on the ‘Book An Appointment’ button on the top right of the screen and get yourself assessed. Either way, read on to learn more.

What is Pelvic Organ Prolapse?

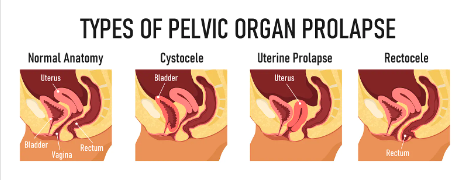

Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP) is when the pelvic organs, namely the bladder, uterus, or rectum, bulge into the vaginal canal or in more severe cases, out of the vaginal opening itself. Symptoms associated with POP include a sensation of heaviness or pressure in the vagina, or a feeling like something is falling out of the vagina (often described as feeling like a tampon falling out). The severity of symptoms ranges from person to person and does not correlate directly with the severity of the prolapse itself. This means someone with a relatively more severe prolapse can experience mild symptoms, and someone with a relatively mild prolapse may experience severe symptoms. What matters is that if it is affecting your quality of life, then it should be addressed!

Why Does POP Occur?

POP occurs due to a lack of support to the pelvic organs. There are two types of support: passive and active.

Passive support comes from the vaginal canal, acting as a pillar of support, with the 3 pelvic organs using it like a leaning post. The bladder sits in front, the uterus sits above (directly connected to the vaginal canal), and the rectum sits behind. Depending on how you position yourself and move through the day, the organs will intermittently shift and lean against the vaginal canal, the canal will hold true, and then they may shift away from it.

Active support comes from the pelvic floor muscles. The 3 pelvic organs sit directly on top the pelvic floor, which impacts their positioning. A functional pelvic floor will resemble a trampoline – at rest, it maintains some flexible tension and will be able to hold the organs in a propped up position, decreasing how often they will naturally lean into the vaginal canal.

POP can happen at any point in one’s lifetime, but most commonly is seen after vaginal delivery, or later in life in peri- or post-menopause. The common denominator is changes to the vaginal canal walls and the pelvic floor muscles. In these two scenarios, the vaginal canal walls have lost some of their integrity, and some of the elasticity needed to be the pillar of support. This means that when the pelvic organs temporarily lean into it, the walls can give way and the organs may bulge into the canal. The pelvic floor in these scenarios has either experienced some direct trauma (vaginal childbirth), changes in hormones have affected its strength (menopause), or the resting tension and workload of the pelvic floor muscles has been affected. Ultimately, this changes our ability to actively support the organs. Without it, the pelvic floor may now act like a hammock, contributing to the pelvic organs falling toward the vaginal canal to be the remaining form of support. As you can see, they need each other!

What Can Be Done for POP?

First and foremost, get assessed by a pelvic health physiotherapist! We can help identify if you are presenting with the signs and symptoms of POP, as well as guide you in how to manage it. From the perspective of physiotherapy, our role is to more directly impact the pelvic floor muscles and their contribution to the active support of the pelvic organs.

It is important to understand that pelvic floor contractions (Kegels) may seem like a good idea on paper – “my pelvic floor is weak, therefore I should strengthen it”. And although this is true, our pelvic floor muscles can be over-tense and over-loaded, giving us the sensation of weakness through fatigue. If the pelvic floor is experiencing this, we actually need to learn to let go of tension in the pelvic floor, and decrease its workload on a daily basis. That way, the task of supporting the organs is more feasible. A trained pelvic health physiotherapist will be able to determine which pathway of treatment is right for you.

Pelvic Floor Workload and Pressure

Picturing the pelvic floor in our bodies, we know that it sits within the pelvis, at the very base of our core. It is the deepest layer of our core muscles, forming a closed system. Picture this like a cylinder: our diaphragm at the top, our transversus abdominis (TA) making up the sides, and our pelvic floor at the bottom. Being a closed system means that there is a certain baseline of pressure within the walls, called our intra-abdominal pressure (IAP). One of the roles of the inner core system is to help manage this pressure.

Increases in IAP can come from breathholding (Valsalva maneuver), bearing down, or eating large meals or producing excessive gas in the digestive tract. These are all things that we may encounter on a regular basis, so it is critical that our inner core can manage these changes effectively. In order to do so, the walls of the inner core (the 3 muscles) need to be pliable and flexible. In other words, increases in IAP should result in the muscles expanding to make room for the temporary change, then revert back once the pressure is relieved. If the walls of the inner core are more rigid or tense, increases in IAP will often result in the pressure being pushed directly down onto the pelvic floor. Over time, this can fatigue and weaken the pelvic floor, despite it holding tense and tight. Not only does this increase how much work the pelvic floor has to contract and hold against the pressure from above, it also places pressure onto the pelvic organs, forcing them to prolapse down and out.

What Can Be Done About IAP?

There are two things to think about when improving our inner core’s ability to manage intra-abdominal pressure.

First, we can have an impact on the daily activities that are contributing to increases in pressure:

- Avoid holding your breath (either at rest OR while exercising). Breathe out when you feel the instinct to breathhold!

- Avoid bearing down to empty your bladder or have a bowel movement. Breathe, breathe, breathe and relax your whole body while allowing your bladder and rectum to empty at their own pace.

- Avoid foods that may cause more gas, or eat in smaller and more frequent meals – you can seek guidance on this from a nutritionist, dietician, or naturopathic doctor, too!

Second, we can have an impact on the flexibility of the walls of our inner core. This refers to their resting level of muscle tension, and encouraging them to be in a state of “ebb and flow”. If our muscles are gently contracting and relaxing, they cannot simultaneously be rigid. One of the best ways to impact this is breathing with our diaphragm!

- Breathe in and allow your lower ribs and belly to expand, as if the walls of the inner core are inflating, expanding to allow the air to come in.

- Breathe out and allow your lower ribs and belly to “deflate”, allowing them to recoil to their starting position without effort.

- And so begins the ebb and flow pattern with each breath!

Another important habit to change is actively gripping the muscles around the core:

- Abdominal wall: check to see if you are clenching your abs throughout the day. We often do this as a habit for aesthetic reasons, but it eventually trains the abdominal wall (and therefore TA) to be over-tense even at rest.

- Glutes: check to see if your bum muscles are clenching, too! Though the glutes aren’t part of the pelvic floor, they are deeply connected to it and tensing here can encourage excessive tension in the pelvic floor muscles.

If we can change these habits throughout the day, the resting tension in the walls of the inner core can gradually decrease over time, allowing them to rest in a state of more pliable, elastic fibers. This way, when there is an increase in IAP, all the walls can expand together as a unit to accommodate the pressure, and avoid directing it down onto the pelvic floor.

Remember, none of this will be a quick fix. Habits are difficult to change, but not impossible! Dedication and working with a pelvic health physiotherapist to help guide you are all you need to make a difference.